David Mann: Converting Sympathetic Strings Into Abstract Art

At David Mann’s solo exhibition Sympathetic Strings, the artist drew a rich visual and metaphorical connection between his art and sympathetic strings. READ MORE

David Mann: Sympathetic Strings

Margaret Thatcher Gallery

By DAVID HORNUNG, JAN. 13, 2016

David Mann explores the evocative properties of color and light as he works in the gap between abstraction and representation.READ MORE

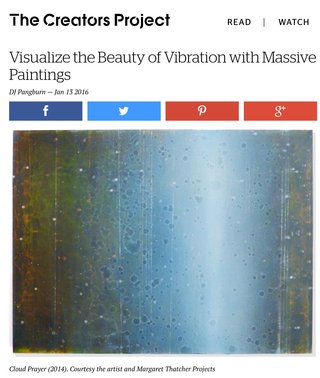

Visualize the Beauty of Vibration with Massive Paintings

DJ Pangburn — Jan 13 2016

New York-based artist David Mann has been making art for decades, with his most recent work exploring abstract shapes configured in such a way that they appear both microscopic and galactic. READ MORE

AESTHETICA

5 To See This Weekend. David Mann, Sympathetic Strings, Thatcher Projects, New York. READ MORE

Article on David Mann Big Bang Effects

BY ELIZABETH LICATA

Is this imagery that you would see through a powerful microscope or a powerful telescope? The colors and shapes are probably more fantastic than could be viewed through device, but they do suggest either molecular or celestial activity. READ MORE

Interview in December Issue of ArtFile Magazine by Alicia DeBrincat

I WAS LUCKY ENOUGH TO MEET DAVID MANN WHILE EARNING MY MFA DEGREE AT PARSONS THE NEW SCHOOL FOR DESIGN, WHERE DAVID HAS TAUGHT FOR THE PAST TWENTY TWO YEARS. SINCE THEN, HE HAS BECOME A WISE AND GENEROUS MENTOR TO ME, SOMEONE I FIND TRULY INSPIRATIONAL BECAUSE OF HIS LUMINOUS AND EVOCATIVE PAINTINGS, HIS PASSION FOR ART, AND HIS COMMITMENT TO HIS WORK AS AN EDUCATOR. IN THE MIDST OF HIS RECENT SOLO SHOW AT MCKENZIE FINE ART, DAVID AND I HAD THE CHANCE TO SIT DOWN TOGETHER IN HIS BROOKLYN STUDIO TO DISCUSS HIS WORK. http://www.artfilemagazine.com/David-Mann

Review by Jonathan Goodman in Art in America

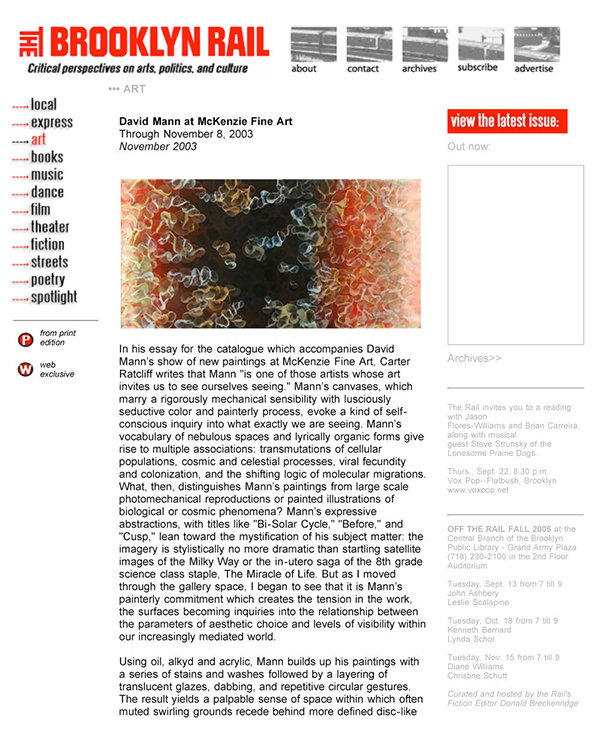

Review by Denise McMorrow in Brooklyn Rail

Essay by Carter Ratcliff

Face to face with a painting, we want to know first of all how it came into being. We wonder about technique, which is always fascinating, but what we really want to know is how a painter’s purpose guides technique. What, for instance, is David Mann doing with his glazes of color? In earlier times, glazes gave luminosity to images of bodies or clouds or even the sky. As fresh as Mann’s art is—and it is only in our era that paintings like his are imaginable—he has a connection to this earlier tradition, for his layers of translucent color bring the night sky to mind. Of course, the equivalence isn’t perfect. These fields of dark light look more like the grounds of painterly possibility.

Mann’s backgrounds absorb his painterly touch into a gleaming smoothness. Asserting its independence, his touch becomes gesture and produces vast populations of swirling, shimmering, flickering shapes. One thinks of teeming biological energy as revealed by the microscope. A macroscopic reading is just as compelling: painting at the scale of cosmography. From the heroic tradition of postwar American abstraction, Mann has learned elasticity of scale. In the pictorial space opened up by Jackson Pollock and Clyfford Still, the infinitely large is the infinitely small—or the other way around. It is up to you, for that is the point of the tradition Mann has extended into the present: to remind you of the freedom you exercise in making sense of what you see. This is the viewer’s share of the freedom Mann exercised when he made these paintings.

Smoothed into invisibility, entangled in its own complexity, floating into the stark clarity of total independence—Mann’s gesture runs the gamut. Sometimes I focus on a single shape, fascinated by the translucency that lets me read it as flat and, at the same time, as a form driven by its own complexity to deny the very idea of flatness. Widening my focus, I see how these forms interact. Or resist interaction. How the shapes coalesce into patterns or don’t. Each painting strikes its own balance between order and randomness (or the appearance of randomness, because everything is deliberate here). At one extreme, Tonic has the scattered look of alloverness in the Pollock manner. In Cluster, by contrast, I feel that the pulse of pictorial energy is about to settle into a composition—stable and balanced and reassuring.

What reassures us, ultimately, is Mann’s command of his medium. His colors are rich, almost iridescent, yet there is something stringent about his deployment of form. With spots of color, he marks the surface of the canvas—rather, he insists that these are canvases, works of art, not pictures of things seen through a lens. All talk of amoebae or galaxies is metaphorical, a roundabout way of getting at the purpose of Mann’s luminosity, which is to illuminate our reading. He is one of those artists whose art invites us to see ourselves seeing, and of course there are times when we simply drift into the pleasures of a paradox: the lush stringency of these astonishing canvases.

—Carter Ratcliff

Essay by John Zinsser

The Revolution has Begun

May 4, 1970, Kent State University. Four student war protesters are shot dead by the National Guard. David Mann, then an undergraduate there, remembers calling his parents that day and telling them, “Mom, Dad, the revolution has begun.”

For Mann, this day marked “the ends of certain kinds of faith and belief.”

Strong belief systems drive good abstract painting, and Mann—just beginning his life as an artist—found himself poised at a moment of powerful generational shift.

Growing up Buffalo, N.Y. in the 1950s, Mann watched his father run a silkscreen printing business. Here, images were reproduced photomechanically, using screens and squeegies. In an age of pre-Warholian irony, Mann was exposed to a commercial art-making process that reflected the decidedly American ethos of mass production.

The local Albright-Knox Art Gallery, with its preeminent collection of Abstract Expressionist works, offered a different kind of paradigm for Mann. Featured artists such as Clifford Still and Jackson Pollock drew from their private unconscious experiences to make large-scale works of unique iconic quality.

When Mann later returned from Ohio to Buffalo in the 1970s for his graduate studies at the University of Buffalo, his mentor, Seymour Drumlevitch, a collagist of a decidedly 1950s abstract bent, further schooled him in the ethos painting as a means of internal self-examination. But the school’s visiting artists from New York City, Richard Serra and other hard-line Minimalists, brought with them a whole new antithetical philosophy.

The revolution had indeed begun.

The group of paintings assembled for this exhibition deal directly with this biographical trajectory.

Mann allows himself an intuitive vision that is intensely lyrical and private. Yet his technical means are literal: his process-driven procedures, his use of unadulterated chromatic color. He weighs the inwardness and touch of Abstract Expressionism against a mediated, post-Minimalist mechanical aesthetic.

The New Margin, 2001, with its transparent glazes of violets and blues, suggests a kind of deep space. Free floating bubble-like shapes in the foreground allude to biological form, akin to underwater flora in their crenulated delicacy. These quasi-figures seem caught mid-flutter. There is the sense of the photographic, of movement arrested in a moment of time. Though several light sources are apparent, the quality is stroboscopic, that of cold scientific analysis.

In the horizontally-formatted Spanish Manners, 2001, the layered orchestrations of reds (alizarin crimson, burnt umber, napthol red, perylene red) make for a cherry-sweet hothouse feel. Wispy tendrils render specific orchid-like plant forms throughout. The custom colors of California car culture have been transplanted into a sweeping primordial landscape. Color is obliquely layered here, less differentiated, more saturated overall. Mann is showing us the beginning of life and the end of life at the same time. The forms have an environmental integrity while the color suggests toxicity and the immanence of biological threat.

In these works Mann demonstrates that paint, if left to its own devices, has a kind of nature of its own. And if it has a nature, it’s a poisonous nature: one that represents the presence of man, of culture, of independent thought.

Throughout this confident new body of paintings, Mann weighs the illusionism of depth-of-field space against the literalness of paint-as-paint. The inherent tensions of this twin polarity elicit a pure beauty. Mann, drawing from his longtime life experience as an abstract painter, has arrived at a body of work that succeeds on both personal and analytic terms.

—John Zinsser